Stomata

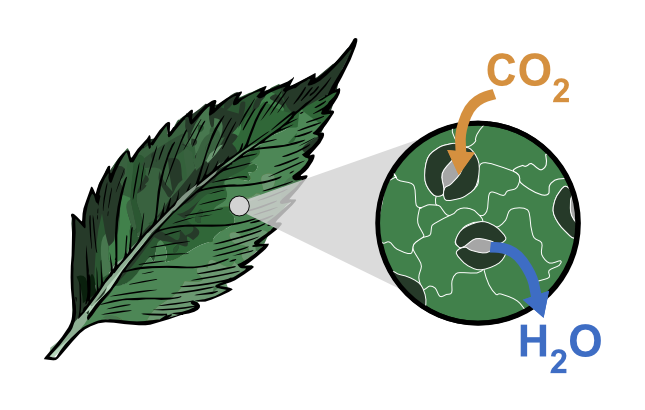

Stomata (singular: stoma) are microscopic, adjustable pores found on the surface of most land plants. If you imagine a plant leaf as a living “skin,” stomata are its controllable “valves” connecting the inside of the plant to the outside air. Through these pores, plants take in carbon dioxide (CO₂) for photosynthesis, release oxygen (O₂) as a by-product, and lose water vapour (H₂O) through transpiration.

Stomata sit at the centre of an unavoidable trade-off:

- Open stomata → more CO₂ enters → potentially higher photosynthesis, growth, and yield, but more water is lost.

- Closed stomata → water is conserved, but CO₂ entry is restricted → photosynthesis slows and leaves can heat up.

1) A gentle introduction (school-friendly)

What do stomata do?

Stomata help plants:

- Breathe (gas exchange): CO₂ in, O₂ out.

- Move water: transpiration helps pull water from roots → stems → leaves.

- Stay cool: evaporation cools leaves (like sweating).

- Respond to the environment: light, heat, drought, humidity, CO₂ levels, and even microbes.

Where are stomata found?

Most commonly on leaves, but also on:

- Green stems and petioles

- Floral tissues in some species

- Reproductive structures in some early-diverging land plants

How small are they?

Stomatal pores are typically tens of micrometres across. You cannot see them clearly without magnification, but a leaf may contain thousands to hundreds of thousands of stomata depending on species and growth conditions.

Did you know? (transpiration scale)

Transpiration through stomata can be enormous at ecosystem scale. Exact values depend on species and conditions, but the key idea is that many tiny pores collectively control very large water fluxes.

2) Where stomata sit in a leaf (leaf anatomy context)

A typical leaf has:

- A protective cuticle (waxy outer layer)

- The epidermis (outer cell layer)

- Mesophyll tissue where photosynthesis happens

- Intercellular air spaces that distribute CO₂ within the leaf

- Veins: xylem brings water; phloem exports sugars

A stoma forms a gateway: outside air ↔ stomatal pore ↔ substomatal cavity ↔ leaf air spaces ↔ mesophyll cells ↔ chloroplasts. This pathway matters because CO₂ must diffuse from the atmosphere to chloroplasts, and water vapour diffuses out in the opposite direction.

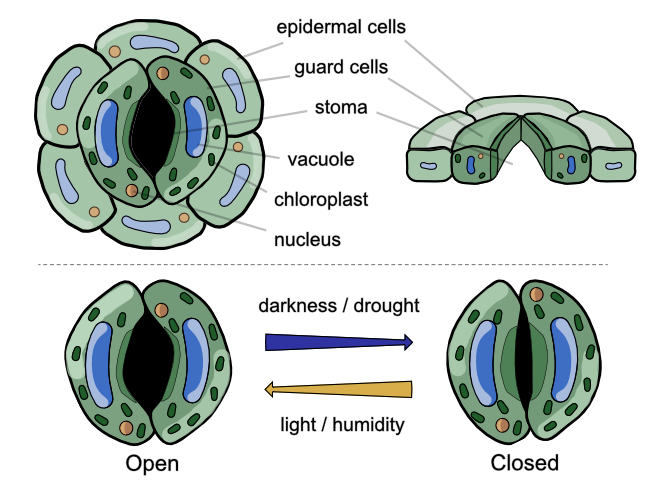

3) The stomatal complex (structure)

A stoma is more than a hole. The full “stomatal complex” typically includes:

- Guard cells: paired cells controlling the pore via turgor changes.

- The pore (aperture): the adjustable gap between guard cells.

- Subsidiary cells (many species): neighboring cells that can support mechanics and speed responses (notably grasses).

- Substomatal chamber: an air-filled cavity beneath the pore connecting to air spaces.

Why are guard cells special?

- They contain specialized ion transporters and signaling components.

- They often contain chloroplasts (many epidermal cells do not).

- They have reinforced cell walls and microfibril architecture that converts swelling into bending.

4) Types and morphology

Guard-cell shape (two major categories)

- Reniform (kidney-shaped): common in many eudicots, ferns, and gymnosperms.

- Graminaceous (dumbbell-shaped): characteristic of grasses; often paired with subsidiary cells and fast kinetics.

Classification by subsidiary-cell arrangement

Common stomatal types used in taxonomy (examples; terminology can vary between keys):

| Type | Description | Often seen in (examples) |

|---|---|---|

| Anomocytic | No obvious subsidiary cells; surrounded by ordinary epidermal cells. | Ranunculaceae, Cucurbitaceae (examples) |

| Anisocytic | Three subsidiary cells; one is distinctly smaller. | Brassicaceae (examples) |

| Paracytic | Subsidiary cells parallel to the long axis of the pore. | Rubiaceae, Fabaceae (examples) |

| Diacytic | Two subsidiary cells; common wall perpendicular to the pore. | Caryophyllaceae (examples) |

| Actinocytic | Surrounded by a ring of radiating cells. | Ebenaceae (examples) |

Distribution on the leaf

- Hypostomatous: mostly lower surface (common; often reduces evaporative demand).

- Amphistomatous: both surfaces (often in high light, high CO₂ demand environments).

- Epistomatous: mostly upper surface (common in floating aquatic leaves).

5) The physics of opening and closing (biomechanics)

Stomatal movement is a mechanical outcome of osmotic changes (solutes move → water follows), turgor pressure changes, and cell-wall architecture (anisotropy, thickening, microfibril orientation, pectin status).

Radial micellation (the “barrel hoop” idea)

Guard cells have cellulose microfibrils arranged roughly like hoops around a barrel. This restricts expansion in one direction but allows expansion in another. As guard cells take up water and elongate, they bow outward and the pore opens.

6) Guard-cell osmoregulation (the core mechanism)

At the cellular level, stomatal aperture is controlled by guard-cell osmotic potential and thus turgor. A simple identity is:

Where Ψs is solute potential (more negative with more solute), and Ψp is pressure potential (turgor).

Opening (simplified sequence)

- Stimulus (often light, especially blue light) activates guard-cell signaling.

- Plasma membrane H⁺-ATPases pump protons out.

- Membrane becomes more negative inside (hyperpolarized).

- K⁺ influx increases (with counter-ions such as Cl⁻ and/or malate²⁻).

- Water enters (often aided by aquaporins) → guard cells swell → pore opens.

Closing (simplified sequence)

- Stress signals (ABA, high CO₂, darkness, high VPD, etc.) activate closure pathways.

- Anion channels open → anions exit → membrane depolarizes.

- Outward K⁺ channels open → K⁺ exits.

- Water leaves → guard cells shrink → pore closes.

Key solutes involved

- K⁺: major osmotic driver

- Cl⁻ and NO₃⁻: counter-ions

- Malate: organic anion linked to metabolism

- Sucrose: can contribute strongly later in the day

- Starch metabolism: buffers carbon and osmolyte availability

7) Signaling and regulation

Stomata integrate multiple signals simultaneously. In real leaves, stomatal behaviour is not an on/off switch but a continuously adjusted aperture.

Light

- Blue light is a strong direct driver of opening (guard-cell signaling).

- Red light often promotes opening indirectly by stimulating mesophyll photosynthesis, lowering internal CO₂.

- Circadian rhythm: responsiveness changes with time of day even under constant conditions.

CO₂

- Stomata generally open when internal CO₂ is low (to acquire more) and close when it is high (to conserve water).

- CO₂ responses interact with light, VPD, and leaf energy balance.

Water status and atmospheric dryness

- Soil/plant water status and hydraulic signals influence closure during drought.

- VPD (vapour pressure deficit) quantifies “drying power” of air; high VPD often drives partial closure to prevent runaway water loss.

Temperature, pollutants, and microbes

- Stomata influence leaf temperature via evaporative cooling, creating trade-offs under heat + drought.

- Ozone (O₃) can enter through stomata and cause oxidative stress.

- Many pathogens enter via stomata; plants can close stomata as part of innate immunity.

8) ABA-mediated stomatal closure (advanced but essential)

ABA (abscisic acid) is a canonical drought signal. A widely taught “core” module is:

The exact wiring and contributions of Ca²⁺, ROS, and additional kinases/phosphatases vary by context and are active research areas.

9) CO₂ signaling in guard cells (modern research focus)

CO₂ signaling is not purely passive diffusion. Guard cells sense CO₂-related cues and translate them into ion-channel control. Advanced literature often discusses carbonic anhydrases (CO₂ ↔ HCO₃⁻), kinase pathways, and anion-channel regulation.

10) Stomata in different photosynthetic strategies (C3, C4, CAM)

C3 (most plants)

- Daytime stomatal opening is common.

- Photorespiration can rise under heat/drought when stomata close and internal CO₂ drops.

C4 (many grasses and some crops)

- CO₂ is concentrated in specialized tissues, often enabling lower conductance for similar carbon gain.

- Often higher water-use efficiency than comparable C3 species.

CAM (many succulents, epiphytes)

- Stomata are often more open at night; CO₂ is stored as organic acids.

- Daytime stomata can remain more closed while photosynthesis uses stored CO₂.

- A strong adaptation to extreme water limitation.

11) Development and genetics

Stomata form through a regulated developmental program. Many plants exhibit a “one-cell spacing rule” (stomata separated by at least one epidermal cell), emerging from signaling between lineage cells and neighbors.

Arabidopsis lineage (conceptual): SPCH → MUTE → FAMA

A common teaching model uses bHLH transcription factors:

Patterning is regulated by peptide–receptor signaling: EPF1/EPF2 (negative regulators) and EPFL9/Stomagen (positive regulator) interacting with receptor families (e.g., ERECTA/TMM modules).

12) Evolution and ecology

Evolutionary timeline (high level)

- Early land plants: stomata appear in the fossil record hundreds of millions of years ago; key for terrestrialization.

- Bryophytes: stomata often on sporangia; roles may include drying/ventilation rather than leaf gas exchange.

- Liverworts: many lack true stomata, using fixed pores that cannot close.

- Seed plants: stomata abundant on leaves with active regulation and diversification of forms.

Global impact (why stomata matter for climate)

Stomata regulate large fractions of terrestrial water and carbon exchange. Reported global numbers vary by model and dataset, but the qualitative point is robust: stomata strongly couple the water and carbon cycles.

13) Measuring stomata (from classroom to lab to big data)

Basic methods

- Clear nail varnish/acetate impressions of epidermis

- Light microscopy for counting and density estimates

Standard quantitative traits

- Stomatal density (SD): number per unit area

- Stomatal index (SI): stomata / (stomata + other epidermal cells) × 100

Where S = stomata count, E = other epidermal cell count (in the sampled area).

Physiological measurement

- Gas exchange systems (IRGA): measure assimilation (A), transpiration (E), and stomatal conductance (gₛ)

- Porometers: estimate conductance directly

- Thermal imaging: infer transpiration-driven cooling

High-throughput imaging and AI (the StomataHub connection)

- Object detection (e.g., YOLO/R-CNN family): identify and count stomata quickly.

- Segmentation: outlines stomata/pore for area and morphology measurements.

- Scale: thousands of images → enables larger genetic studies and comparative biology.

14) Frontier topics (for advanced readers)

- Engineering stomatal density to tune water-use efficiency vs productivity trade-offs

- Speeding kinetics (opening/closing) to improve carbon gain under fluctuating light

- Guard-cell wall mechanics (pectins/microfibrils) as functional levers

- Signal integration (ABA × CO₂ × light × VPD × temperature × defence) in realistic field conditions

- Ozone stress and “stomatal sluggishness”

- Scaling from pore diffusion to canopy and Earth-system models

Glossary

References & suggested reading

This page is written in our own words, based on standard plant physiology and developmental biology concepts. For authoritative treatments, start with plant physiology textbooks and well-cited review papers.